Business Model Matters

/You wouldn't hire a maid service that offered to clean your house for free, and you probably wouldn't trust a storage company that didn't want to be paid to hold onto your stuff, either. We're taught from a young age not to take candy from strangers, and that a free lunch is never as free as it seems. And yet, for some reason, we still take the candy every day, and get angry when we learn there's a catch.

Let's start with two basic assumptions. First, valuable things take time and energy to make. Second, over the long term, no one can afford to give away for free something that's costly to make. If you're on board with those, then you should be okay with the idea that valuable things - at least in terms of the products and services that make up our economy - have to cost something. That means that every "free" lunch, in some way and over some time, is gonna get paid for.

Exactly how lunch gets paid for is at the essence of an organization's business model. And although most people who aren't managers or entrepreneurs or academics don't pay them much attention, business models are fascinating: at the end of the day, they're what govern what products we get to use, what those products look like, and how much they end up costing us.

We don't usually pay much attention to business models because in the past we didn't need to. An orange was an orange and it cost 10 cents. Hotmail was technically free, but there were banner ads all over the page - that was the catch and it was pretty obvious. Life is easy when its easy to see how the strings attach.

But today's world is more global, more complicated, and more connected. That makes it a lot harder to see where the strings are and what you're really paying to use a product. Google's Gmail is a good example. It's free to use and the ads are pretty unobtrusive. But Google also gets to keep and use the data it collects - how much does that end up costing you? Retailers may give you a discount for "liking" them on Facebook, but then get to to use your name in subsequent promotions. Is losing control of your voice on Facebook really worth the extra 10% off? And it isn't just social media: HP and Canon have been selling top of the line printers for under $100 for years, because they know you'll make it up by buying ink. So is a $100 printer with $50 ink a good deal?

This isn't an argument that you often hear, but I believe that understanding a company's business model is the single most important thing you can do to be an educated consumer. A business model stipulates WHY a company makes a product: we're well trained to look at WHAT is made and HOW, but these aren't even close to the full story.

Here are some common examples of what I'm talking about:

- Photo Sharing. Instagram attracted some 30M users over two years by offering a great photo sharing service, for free. But then in December 2012 they announced a that had "the perpetual right to sell users' photographs without payment or notification," which meant that a third party could purchase user's photos for use in advertising without notifying (or paying) the person who took the photo. People weren't happy, but there was no way for Instagram to remain a sustainable service without making money somehow - monetizing people's photos (somehow) had been the plan the whole time. The company eventually backtracked, but not before losing as many as 25% of its users.

- A lot of people join CSAs (community supported agriculture) in order to get baskets of fresh local veggies each week. Essentially, as a shareholder you pony up a few hundred dollars early in the season, then collect later on as things are harvested. Sometimes this will net you a lot of delicious food at a low price, but if something happens on the farm - a hailstorm or an infestation of beetles or a groundhog run amok - you're out of luck. In fact, that's the whole point of a CSA; you're risk sharing with the farmer, who would have otherwise been putting up her own money to finance the farm. The product isn't just the food in this case, it's food + risk (with a dash of support for the local economy thrown in).

- Medical Information. Try searching for something like "hair loss treatment" and seeing what you get. While some legit sites may pop up (WebMD or MayoClinic), you'll also get a host of dodgy looking "hair-information.net" type sites that look like WebMD but with a lot more links to online "pharmacies". The same is true for everything from student loans to investment advice. Someone has gone to the trouble to produce some official-looking content, but why? Either to capture your eyes for advertisers (okay), or to drive you to their partners (maybe less okay). It's also worth knowing that (according to at least one study) under half of the information that turns up in searches like this is actually good.

In fact, there's no shortage of tricky business models for the truly alarmist: Nigerian prince email scams, pyramid schemes disguised as women's empowerment, and potentially a lot of data-stealing apps in the iOS and Android markets. Buying any one of these products without understanding how the underlying business works could leave you an unhappy camper - and probably a bit poorer too. Of course, not all business models are attempts at trickery, even the most convoluted ones. But understanding how a business model works is the only way to know what you're getting, and to ensure that you're not accidentally signing up for an unexpected surprise.

It's also the only way to beat the system. We said earlier that there's no such thing as a free lunch, but this is only partly true. Going back to our original assumptions, a company spending $X to make a product expects to receive at least $X in return. But the value of that $X may be in the eye of the beholder. Being able to use your name in advertising or mining your emails for secrets might be worth $X to the company, for example, but if those things don't bother you then the $X that the company receives actually seems like a lot less than $X to you.

In fact, this is the basic idea underlying economics. We own things - our time, names, or data - that can be traded to others who value those items more than we do. We trade our time for money, for example, which is then traded for food, housing, and concert tickets. If someone wants something we have more than we care about keeping it, there's an opportunity for a trade that makes everybody happy. Thus, if you really want to be connected with friends and don't mind having some analysts poke around your data to see what products you like, Facebook and GMail are great products. Lunch isn't exactly free, but it isn't exactly full price either.

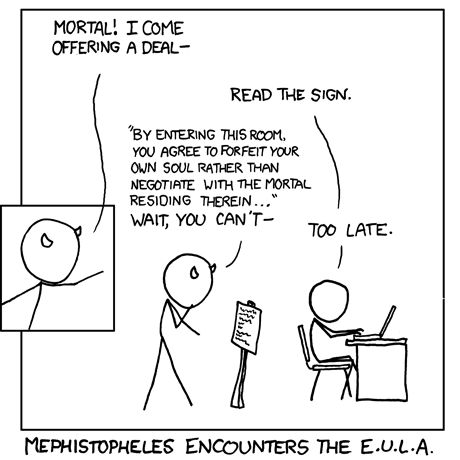

So back to the original argument: understanding how to make that trade, and not paying too much of your money or privacy or time to a company that's savvy enough to get what it wants without offering enough in return, means understanding how and why companies make the products that they do. And that means paying attention to their business models - even when that requires actually reading the license agreement before clicking "I agree."